Conditioning and the Inner World

Conditioning is something we meet from the day we are born. It’s the way the world around us shapes us. We get something if we meet the conditions. For example, if we follow the rules in school, we can be part of a community, earn rewards, and make our parents proud. In this way, conditioning can give us a sense of belonging, reassurance, and safety.

The human mind works in structures and habits, and its main program is survival. Because of this, the human mind naturally aligns with conditioning. As J. Krishnamurti wrote: “The mind, the brain is conditioned in the culture it has grown — religiously, psychologically, socially, economically, family and so on.” (source)

Conditioning has its purpose, especially in childhood. As children, we depend completely on adults — both for physical safety and emotional connection. In that stage, conditioning can be a good thing, providing protection and security. It can even work like an autopilot in emergencies, without shutting down curiosity, creativity, or emotional depth.

Examples of protective, healthy conditioning:

- Looking both ways before crossing the street or locking the door at night.

- Saying “please” and “thank you” automatically, respecting personal space, or waiting your turn in a queue.

- Taking a deep breath before responding in conflict because you’ve practiced it enough for it to become second nature.

- Washing your hands before eating or brushing your teeth before bed.

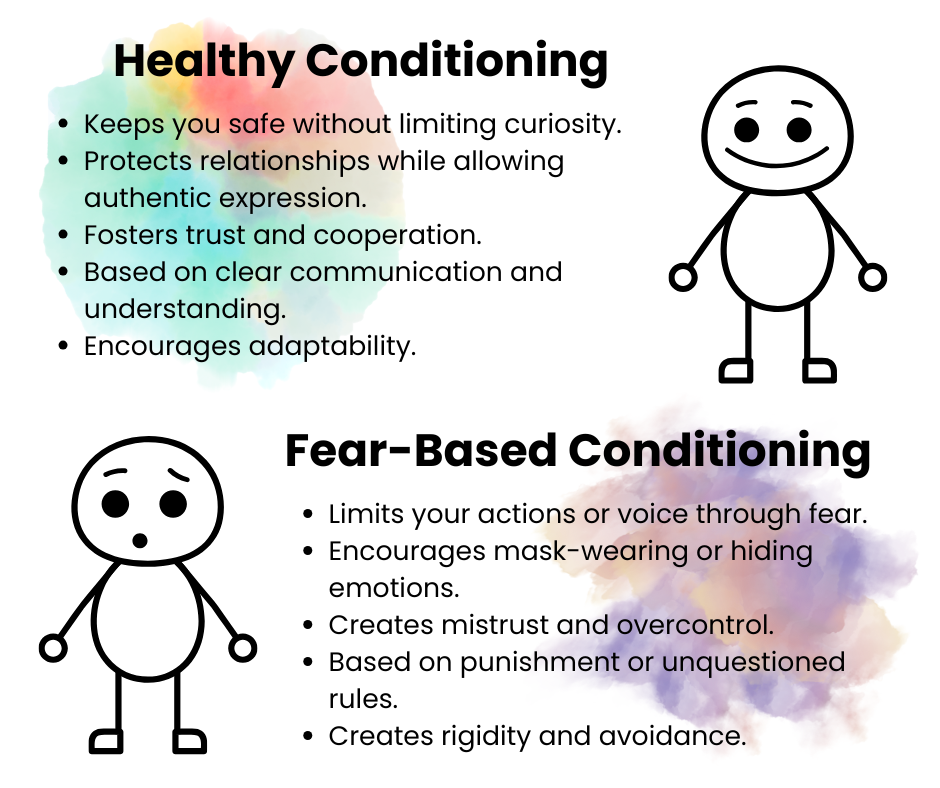

However, over time, conditioning can evolve beyond protection into control — shifting from a safety mechanism to one driven by fear and deprivation. This kind of conditioning interferes deeply with our inner world. It makes us wear masks, or even create a false self.

Examples of limiting, fear-based conditioning:

- When safety habits go too far and you are taught: “The world is dangerous, don’t trust anyone.”

- When social courtesy becomes: “Never show disagreement” or “Don’t express your real feelings.”

- When “staying calm” means you avoid or numb your true emotions.

- When daily self-care or routines become obsessive, fear-driven, or a source of anxiety.

As a parent, I sometimes struggle with conditioning my child. I’ve noticed that when I carry fear or anxiety — and I’m unaware of the roots of my own conditioning — I inevitably pass that fear and anxiety to him. But when I can clearly and calmly explain the rules, the causes, and the effects (and repeat them a hundred times if necessary 😀), the result is “good conditioning” that does not separate him from his authentic self.

How do I know the conditioning was good? For me, the sign is when my son can ask questions and express his emotions about the topic. Even so, I’ll only get the full feedback when he becomes an adult.

Interestingly, one of the best ways to understand conditioning is through animal training. In horse training, for example, conditioning is extremely visible. Horses, as prey animals, have a strong flight response when they feel fear or anxiety. When their conditioning is healthy, they understand the rules and signals, trust their rider, and can face frightening situations calmly. But when training is based on fear and punishment, and lacks clear communication, the flight response can be so extreme that it becomes life-threatening — for both horse and rider.

The more we notice conditioning — in ourselves, in others, and even in the animals we train or care for — the more clearly we can see the difference between what protects and what restricts.

If you want to experience this distinction in a living, breathing way, try observing or even participating in animal-assisted coaching or training. Animals have no masks and respond directly to the energy and clarity they receive. They can mirror back to us whether our approach is based on trust or on fear.

In our daily lives, we can use this same awareness: pause and ask, “Is this rule or habit protecting me, or is it keeping me small?” The answer can help us keep the useful conditioning — and gently unlearn the rest.